Jean-Michel Basquiat: Black Art Criteria vs. Eurocentric American Art Criteria Part 2 by @MelanieCoMcCoy

NOTE TO READER: This is a series so be mindful that this post is a continuation of a previous post. Enjoy- Melanie “CoCo” McCoy

After being told that he should consider doing more art at an extensive level, Basquiat took it seriously and his work was featured along with other artists in a group show. Critics praised his work for it was unique. His work consisted of stick and animal figures, words (which were often crossed out or missing a letter) and scribbles. It seemed as though anyone could do what Basquiat did, but at a certain level that no one could do such a thing. His work was child-like; innocent. Viewers and critics could feel the emotion in his work. It was not necessarily to be understood with the naked or even the critical mind, but everyone could connect with it. His work appeared to be all over the place, yet there was something extremely organized about his style. Many to date call Basquiat a genius.

The Art Story Foundation described his work by stating:

Despite his work’s “unstudied appearance, Basquiat very skillfully and purposefully brought together in his art a host of disparate traditions, practices, and styles to create a unique kind of visual collage, one deriving , in part, from his urban origins, and in another more distant, African-Caribbean heritage.

There were several references in his art from great Eurocentric artists such as Michelangelo Buonarroti, Pablo Picasso, Leonardo Da Vinci and various others. Basquiat even quoted Michelangelo’s famous, “Believe it or not, I can actually draw.”

Upon Basquiat’s arrival he was part of the Neo-Expressionism movement along with well-known artist Julian Schnabel, who some say Basquiat was not very fond of. Basquiat reached stardom as a premiere artist and some feared that it was all happening too fast for him. Others feared that Basquiat was being exploited racially and financially by critics and his artistic peers.

In 1993, Artforum International published an article written by Lorraine O’Grady entitled “Basquiat and the Black Art World.” O’Grady didn’t negatively critique Basquiat’s work, but criticized the art world’s stances and critiques on Basquiat. She spoke on the 1992 draft pick of well-known basketball, Shaquille “Shaq” O’Neal, who was the number one draft pick of that year. That year “Shaq” had “limitless prospects” and appeared to be a “winner” as explained by O’Grady. She states in the article, “His situation seemed to set light on the art world’s own black-player-of -the-moment. For there is no doubt that the most bizarre aspect of the recent Jean-Michel Basquiat retrospective at New York’s Whitney Museum of American Art was its aura of sport. Analysis of the work was put on hold pending results of two different horse races.”

O’Grady criticizes buyers and critics for their Eurocentric way of colonialism:

First: could Basquiat’s prices hold with this much exposure? Answer: yes. The match race between Basquiat and Julian Schnabel continues. At the big New York and London auctions following the opening, Schnabel’s best was $165,000; a Basquiat made $228,000. His prices are at 50 or 60 percent of the earlier bull market and steadily rising. His work has become more, rather than less, financially interesting now that its obsessions with colonialism, creole am, and history can be plugged into the market’s three-year-old concern with multiculturalism.

O’Grady’s article mirrors another one of Du Bois’ essays entitled “Criteria of Negro Art.” Both black and white audiences were looking at Basquiat to be a multicultural savior. In the early twentieth century, black people were hoping that with hard work they would be accepted into the white American world. It was learned that no matter how hard they worked, they could not escape racism or prejudice in the Eurocentric world. This same principle applied to those artists who were black.

Du Bois wrote:

“With the growing recognition of Negro artists in spite of the severe handicaps, one comforting thing is occurring to both white and black. They are whispering, “Here is a way out. Here is the resolution of the color problem. The recognition accorded [Countee] Cullen, [Langston] Hughes, [Jessie] Faucet, [Walter] White and others shows there is no real color line. Keep quiet! Don’t complain! Work! All will be well!””

Du Bois proposes the questions, “What has this Beauty [black aesthetic] to do with the world? What has Beauty to do with Truth and Goodness—with the facts of the world and the right actions of men?” He says that artists “rush to answer “Nothing”.” Du Bois explains that as an artist he holds an obligation to the truth. He states, “I am one who tells the truth and exposes evil and seeks with Beauty and for Beauty to set the world right.”

Untitled (History of the Black People), Jean-Michel Basquiat, 1983

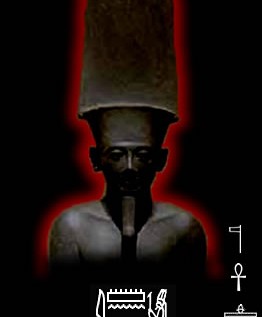

In 1983, Basquiat created a piece that was loaded with large meanings entitled Untitled (History of the Black People). According to Andrea Frohne in “Representing Jean-Michel Basquiat,” the meaning behind the painting could possibly be his reclaiming of Egyptians into black ancient civilization; Egyptians are Africans. Basquiat felt that white historians were rewriting history by separating Egyptians from Ancient Africa, dismissing that Egypt is in West Africa. On the left side of the paneled painting there are drawings of African masks. There is a high presence of African imagery, because he is embedding into the viewer’s mind that Egyptian pharaohs and queens were black. On the right of the painting the words “Memphis Thebes Tennesee [Tennessee]” are written in black on top of white paint. Thebes is a city in Ancient Egypt, which is also a Greek name. Historically, Memphis, Tennessee holds a painful past for the black race. It was one of the most racist cities in the U.S. Before racist segregation laws were implemented, Memphis was also apart a large slave-trade market. Memphis, Tennessee is also the place where activist Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated. The white muddle of paint where the words are written on top, could possibly be symbolic for the gentrification and “white-washing” of black people’s history. This does not overshadow the painting for the viewer can see that nobly in the middle stands a golden figure. Gold is the color of wealth and it triumphs over everything existing in the entire artwork.

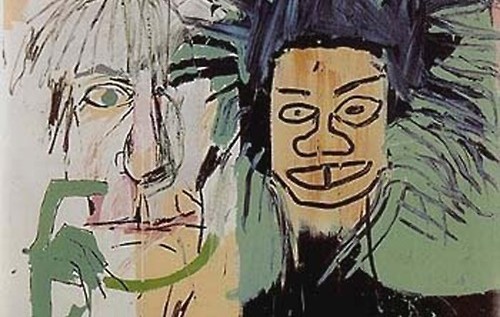

Basquiat and well-known pop artist, Andy Warhol, became very close. Many believe that Warhol was using Basquiat, but others believe that their relationship was genuine. Together they had a popular culture art show which contained Americanized logos and familiar cartoon characters.

Companion (Passing Through), KAWS, Philadelphia, 2013

Today this sort of style can be seen in the work of graffiti artist turned popular culture artist, Brian “KAWS” Donnelly who graduated from the School of Visual Arts in New York in 1996. One of the major parts of KAWS’ life that he has in common with Basquiat is that in Jersey City, KAWS also started his career by doing graffiti. People just like the people of New York City in the late 1970’s, wondered who KAWS was. KAWS is most famous for his sculpture of a popular culture inspired creature that he calls Companion. Companion has the body of the cartoon character Mickey Mouse, with an inflated skull and cross-boned head. Since KAWS success withCompanion he had a clothing line called Original Fake, a toy line, and a touring “Companion” in an exhibit called Companion (Passing Through). In many ways, KAWS is like the white Basquiat. He has been praised by the visual art industry and music industry; like Basquiat. There works are very different in terms of style, execution and technique, but alike in that they both use child-like influences to create their pieces. It is possible that KAWS received his influence from the art explosion of the 1980’s which included Basquiat.

In chapter 1 of Unpackaging Art of the 1980’s entitled 1980s “Art Polemics and Their Legacy: Reactions to Market Hype and Artististic Trends,” Allison Pearlman dissects the consumerism, politics, and commercialization of 1980s art. As raw of a talent KAWS is in a lot of way KAWS has become commercialized, which is not necessarily always a negative issue.

Pearlman states (p.9)

The emergence of Julian Schnabel, David Salle, Jean-Michel Basquiat, Keith Haring, Peter Halley, and Jeff Koons as “arts stars” in the 1980s aroused American art critics most explicit fear of the time: that art no longer opposed consumer culture. They expressed their anxiety in scores of impassioned articles between 1981 and 1987 against the marriage of art and commerce.

Below are the works of a few of the artists that Pearlman mentions:

Day-Glo Prison, Peter Halley, 1981

Miner, David Salle, 1985

Untitled, Keith Haring, 1981

In 2012, music producer, clothing designer, and musician, Pharrell Williams, partnered with the Reserve Channel and created a show called Artst Tlk. The show received various artists like Daniel Arsham. Two of the guests were KAWS and the artist that Pearlman mentions in her book, David Salle. Pharrell, KAWS and David Salle discussed art, its problems, and the critiques of their work made by people.

Art has become more consumer-based, but one of the current issues still remains about what the criteria is for an artist of a black cultural background or of a non-white cultural background. There are numerous restrictions because both black and white audiences demand that the artist’s work show some element of “blackness” if the artist is black. In an essay entitled “The Negro-Art Hokum,” writer, George Schuyler says that “Negro art “made in America” is as non-existent as the widely advertised profundity of Cal [Calvin] Coolidge, the “seven years of progress” of Mayor Hylan, or the reported sophistication of New Yorkers. He poses the question, “How, then, can the black American be expected to produce art and literature dissimilar to that of the white American?” He names many white artists and then black artists to come to the point that their work has been based upon their environment. Schuyler states, “All Negroes: yet their work shows the impress of nationality rather than race. They all reveal the psychology and culture of their environment- their color is incidental. Why should Negro artists of America vary from the national artistic norm when Negro artists in other countries have not done so?” Schuyler during the same time period as Du Bois argues against Du Bois belief that if you are black than your work should be black. This is a similar argument that poet and writer, Langston Hughes makes in his essay “The Negro Artist and The Racial Mountain.” Hughes was angered by young Negro artists and poets who would say, “I want to be a poet- not a Negro poet.” Basquiat said something very similar to the very expression that Hughes is agitated by which was, “I am not a black artist, I am an artist.”

Unfortunately on August 12, 1988, Basquiat died of a heroin overdose at the age of twenty-seven. He tried to fight his heroin addiction, but life became too great and overwhelming for him.” Basquiat’s influences still came from his black cultural background, even though he did not think of himself as a black artist. He exhibited the criteria of black art, but did not allow for people to label him, although they tried and still do. Basquiat remained true to his black and Latino cultural heritage, he sought to reveal honesty and truth to the extent of sometimes losing himself, and through his art was responsible over his community by giving to them true art.

Works Cited

- BASQUIAT, JEAN-MICHEL. “Andrea Frahne.” The African Diaspora: African Origins and New World Identities (2001): 439.

- Basquiat, Jean Michel. The Radiant Child. 2010.

- Bosworth, Patricia. “Hyped to Death: The Short Life of Jean-Michel Basquiat, Graffiti Artist

- Du Bois, William Edward Burghardt. Criteria of Negro art. Crisis Publishing Company, 1926.

- Dubois, WE Burghardt. “The Negro in literature and art.” The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science (1913): 233-237.

- Hughes, Langston. “The Negro artist and the racial mountain.” The Nation122.23 (1926): 692-694.

- Jean-Michel Basquiat: An Interview/ Young Expressionists. Perf. Marc H. Miller and Jean-Michel Basquiat. ART/ New York. N.p., n.d. Web.

- “Jean-Michel Basquiat Biography.” Bio.com. A&E Networks Television, n.d. Web. 29 Apr. 2013.

- “Kaws Biography.” Kaws Biography. N.p., n.d. Web. 29 Apr. 2013.

- O’Grady, Lorraine. “A Day At the Races, Lorraine O’Grady on Jean-Michel Basquiat and the Black Art World.” Artforum International Magazine Apr. 1993: n. pag. Web.

- Pearlman, Alison. Unpackaging Art of the 1980s. University of Chicago Press, 2003

- Pharrell Williams Interviews David Salle & KAWS | ARTST TLK Ep. 2. Perf. Pharrell Williams, David Salle, and KAWS. Reserve Channel. YouTube, n.d. Web. 29 Apr. 2013.

- Rosenberg, Bonnie. “Jean-Michel Basquiat.” The Art Story. N.p., n.d. Web.

- Schuyler, George Samuel. The negro art hokum. Nation Associates, 1926.

- Turned Gallery Commodity.” New York Times (On the Web). N.p., 9 Aug. 1998. Web.

Thank you for another wonderful article.

Where else may anyone get that type of info in such a perfect approach of writing?

I’ve a presentation next week, and I am on the look for such info.

Hello just wanted to give you a brief heads up and let you know a few of the pictures

aren’t loading properly. I’m not sure why but I think its a linking issue.

I’ve tried it in two different web browsers and both show the same results.

Hey very interesting blog!

Jean-Michel Basquiat: Black Art Criteria vs. Eurocentric American Art Criteria Part 2 by @MelanieCoMcCoy http://t.co/jiuwc6qfAV

Jean-Michel Basquiat: Black Art Criteria vs. Eurocentric American Art Criteria Part 2 by @MelanieCoMcCoy http://t.co/j8Ou9LaAcP

Jean-Michel Basquiat: Black Art Criteria vs. Eurocentric American Art Criteria Part 2 by @MelanieCoMcCoy http://t.co/DEPMaaXz9S

RT @JESSfaFUN: Jean-Michel Basquiat: Black Art Criteria vs. Eurocentric American Art Criteria Part 2 by @MelanieCoMcCoy – http://t.co/FbR2BXy2V5

Jean-Michel Basquiat: Black Art Criteria vs. Eurocentric American Art Criteria Part 2 by @MelanieCoMcCoy – http://t.co/FbR2BXy2V5

Jean-Michel Basquiat: Black Art Criteria vs. Eurocentric American Art Criteria Part 2 by @MelanieCoMcCoy – http://t.co/OKe6EE2u3a