In Virginia, Statistics Show A Gap In Race In Gifted Education

Robert Downs has attended Norfolk Public Schools since kindergarten, but it wasn’t until fifth grade that his mother learned of the division’s program for gifted students.

“If it hadn’t been for one of my friends who’s a teacher, I would have never known,” Jamila Downs said. Downs followed up with her son’s guidance counselor, and after an assessment, Robert was enrolled in the gifted program last year.

But the fact that he missed years of gifted instruction pains his mother – as does the notion that Robert, an African American student, may have been overlooked. “He wouldn’t have been identified as gifted if I didn’t go to the office and ask questions about it,” Downs said.

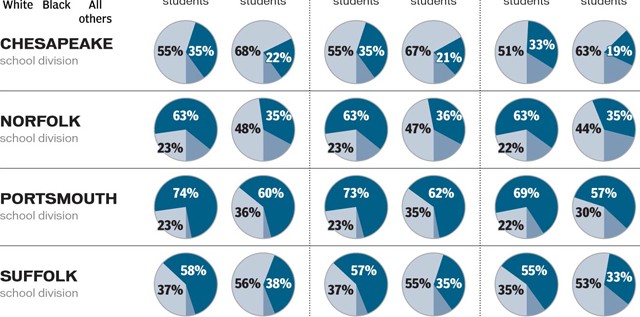

In Norfolk and every other South Hampton Roads division, black students are underrepresented in gifted programs and whites are overrepresented compared with overall school populations, even though experts say gifted traits are shared equally across ethnic groups.

Black children represented 63 percent of Norfolk’s overall enrollment in 2010-11, but only 35 percent of the students identified as gifted were black, according to the state Department of Education’s most recent data. The same data show that under-representation has been consistent across South Hampton Roads schools for years, as has overrepresentation of white children in gifted programs.

The disparity has come to the forefront most recently in Norfolk, where the division is proposing an update of its five-year gifted education plan.

When the plan was presented in August for School Board approval, board member Rodney Jordan asked why it did not put more emphasis on enrolling underrepresented student groups. The board agreed to postpone its vote to give members and the public time to study the plan. The division has since held a public forum and solicited residents’ feedback.

The racial imbalance in gifted enrollment has exasperated some parents, officials and community leaders in other South Hampton Roads cities as well.

“As a minority, we can perform as well as anybody, and we need to be given the resources, meaning good teachers and access,” said George Reed of the New Chesapeake Men of Progress Education Foundation, an advocacy group emphasizing education for African American boys.

In Chesapeake, black students represented 33 percent of overall enrollment in 2010-11, but only 19 percent of gifted students in the latest data. Reed questioned whether the division has lower expectations for black students.

“Is there equitable procedure for identifying these students among all the ethnic groups who will be in the gifted program?” he added.

Chesapeake spokesman Tom Cupitt said in an email that no administrator was available to discuss the division’s gifted program. The division’s gifted plan, posted on the school system’s website, cites the need to increase identification of gifted students from under served groups and gives several strategies to do so.

The state requires all public divisions to offer gifted programs and says assessment tests should be free of bias, but it gives no diversity requirements or guidelines.

That doesn’t mean divisions should just shrug their shoulders over the years-long racial disparity in gifted programs, said Carolyn M. Callahan, a gifted education expert at the University of Virginia. She said poverty, a lack of early childhood learning opportunities at home and cultural differences can mask a child’s gifted traits.

“Every bone of fairness and our ethical responsibility would say we should do all we can to make sure any group of kids has the opportunity to develop their potential to the fullest,” Callahan said.

For Norfolk board member Jordan, the issue is an economic imperative. “We say we want to attract newcomers and high-paying jobs. The more students that we ensure have an opportunity and pathway to maximize their academic potential… it makes our community more attractive to business leaders” as well as families, he said.

The state recognizes that no single trait or test can identify every gifted child, and it requires divisions to use various criteria for discerning potential giftedness.

On its website, the Norfolk division lists common traits of gifted children: compassion for others, high energy, a great sense of humor, a tendency to question authority, excellent memory, rapid learning ability, high creativity and moral sensitivity are some.

Many parents and even teachers might not recognize some of these as hints of a child’s giftedness, said Kelly Hedrick, Virginia Beach’s gifted education director. That can ring true particularly if the same child doesn’t excel at traditionally valued academic tasks, such as reading, she added.

Other factors that can complicate recognizing giftedness include student disabilities, lack of learning opportunities in poorer households, the stereotype that gifted children are white and affluent, and parents’ unfamiliarity with gifted education, she said.

Methods used by local divisions include aptitude tests, teacher and parent referrals, portfolios of student work, past performance and observation of in-class behavior. Every South Hampton Roads division conducts at least one gradewide assessment test, typically in the first or second grade.

Once a student is identified as gifted, the next steps also vary by division.

Students may be clustered with other gifted children in a class that also includes mainstream learners. Or they may attend special gifted programs, such as Norfolk’s Young Scholars and Virginia Beach’s Old Donation Center. Portsmouth’s gifted resource labs work with gifted students in grades three to six two hours a week.

Children in these programs may be instructed at an accelerated pace, receive more content in their coursework, or do research projects that tap and stretch their special abilities. At Virginia Beach’s Kemps Landing magnet school, for example, every sixth-grader takes Latin, the school day is extended, and extracurricular activities include “Future Problem Solving.”

In Norfolk, the proposed gifted-education plan calls for reviewing identification and fair student representation in its first year.

Other aspects of the plan also address underserved student groups, though that may not be obvious, said Lisa Corbin, senior director of curriculum and professional development for the division. “Sometimes as educators we speak in edu-babble,” she said. “That’s why it’s so good to get community input.”

Virginia Beach has spent years training teachers and parents in identifying gifted children, said Hedrick, who acknowledged disparities in her division’s gifted enrollment. The division has a gifted resource expert to work with teachers and parents in every school. Workshops, starting in first grade, are held for parents who know little about gifted traits, she said.

The division also screens all students in first grade to identify gifted children. A second round of screening in grade five was added last year in an effort to identify more minority and low-income students who are gifted.

Nonetheless, some student groups remain underrepresented in the Beach. Blacks constitute 9 percent of gifted students but 25 percent of the total student body.

Ashley K. McLeod, a Beach school board member, called it “a huge concern.”

“I don’t know who’d have the answer as to why African Americans, why they don’t identify more,” she said.

In Suffolk, Tomika Eley, a three-year member of the division’s gifted advisory committee, said she didn’t know about the disparity there until contacted by The Virginian-Pilot. “That definitely does raise a concern,” said Eley, a parent of two gifted children. “I would definitely be interested in exploring to see what we can do to close that gap.”

Portsmouth adopted its latest five-year gifted education plan in May. It calls for strategies over the next three years “that will assist in the identification of groups that are traditionally underserved or underrepresented.”

The plan targets the economically disadvantaged, students for whom English is a second language and “culturally diverse student groups.”

Portsmouth has the smallest ethnic disparity in gifted enrollment of any South Hampton Roads division; black students represented 57 percent of gifted students and 69 percent of the total school population in 2010-11.

“We don’t want to miss anyone or have anyone fall through the cracks,” said Beverly Jackson, Portsmouth’s gifted education supervisor. “It’s just an all-out search, and it’s a continuous one.

“The goal is, how can we do it better so it is not an elitist program, and that it is for all.”

Interviews with students and sometimes psychological assessments are among methods Portsmouth uses to identify gifted children, even when neither a teacher nor parent has raised that possibility.

Jackson said: “I am of the mindset that when I go in school buildings and they say, ‘We don’t have any (gifted) kids in this grade,’ I say, ‘May I take a look? Can I help?’ ”

Steven G. Vegh, 757-446-2417, steven.vegh@pilotonline.com