How Investigating The Murders Of Biggie & Tupac Cost Chuck Phillips His Career

Last week, a trial in Brooklyn started off with a strange twist. At the federal criminal trial of James Rosemond — a/k/a Jimmy Henchman — one of the first things Rosemond’s attorney did was kick an unemployed journalist named Chuck Philips out of the courtroom by naming him a witness in the case.

Philips was a reporter at the Los Angeles Times for 18 years covering crime and entertainment. In 1999, he won a Pulitzer Prize with his colleague, Michael Hiltzik, for a series examining corruption in the entertainment industry. In 1996, he won the George Polk Award for articles about black art and culture in America. A year later, he won a National Assn. of Black Journalists Award for in-depth coverage of the rap music business.

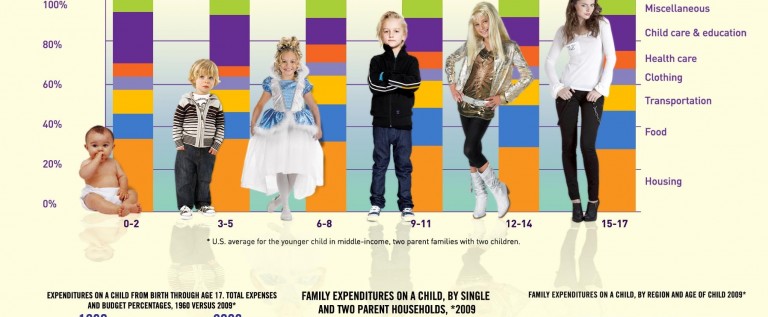

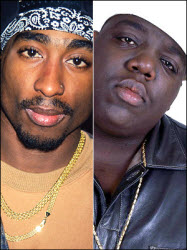

For years, he investigated the shooting deaths of Tupac Shakur and Biggie Smalls, producing some of the most important research into those crimes. And then, in 2008, Chuck Philips’ career in journalism suddenly ended. Now, for the first time, he’s speaking at length about how that came about, and how he became a witness in a federal trial. At the conclusion, we have a statement from the Los Angeles Times, which I received after informing its attorney that we were printing this story — Tony Ortega, Ed.

My name is Chuck Philips. I spent the last ten years of my professional life at the Los Angeles Times investigating the murders of the world’s most important rap artists: Tupac Shakur, and his nemesis, Biggie Smalls. My reporting kept bringing me back to a brutal 1994 ambush at Manhattan’s Quad Recording Studios — a pivotal moment in hip-hop history, a portent of violence to come: a bloody, bicoastal battle that would culminate in the killings of both Pac and Biggie.

|

| Chuck Philips [Photo credit: Dennis Romero] |

The 1994 ambush of Tupac, classified by the NYPD as a robbery, was never solved. No charges were filed. No arrests made. The cops never interviewed Sean “P-Diddy” Combs or other prominent Bad Boy Records employees and associates present at the Quad that November evening. Law enforcement had no love for Tupac or his anti-cop brutality lyrics. From the outset, police showed no interest in solving the crime.

Tupac’s reputation as a troublemaker overshadowed his artistry. On the day of his murder two years later, he was barely 25 — a gifted poet and orator whose unsolved homicide has left a scar on the creative conscience of America.

Pac was not quite the thug he was thought to be by the media. From early on, the artist sought refuge in philosophy. He studied Shakespeare and Neitzsche. Sun Tzu. Machiavelli. Aristocracy did not impress him. Xenophobia annoyed him. He had no time for racism. In Pac’s world, N.I.G.G.A. stood for: “Never Ignorant About Getting Goals Accomplished.”

He was a ladies man too. Handsome. Charismatic. An iconoclast. An outcast. Reared by revolutionaries, he stayed true to his outlaw roots, challenging crooked cops and gangster psychopaths until the end.

And that’s who killed him. Lit him up on Sept. 7, 1996, in a hail of bullets, in front of hundreds of witnesses, on the Las Vegas Strip.

The cops could have cared less. Las Vegas Police Sgt. Kevin Manning, who ran Pac’s murder probe, said Pac’s murder investigation dead-ended for the same reason most gang-on-gang inquiries dead-end, because cop-leery witnesses refused to cooperate.

When I began my murder investigation in 1999, law enforcement’s indifference stunned me. I set out to track down all persons with first hand knowledge of the events. Instead of just talking to detectives, I went to prisons across the nation. I developed relationships with gangsters and their families and friends in areas of LA and NY where drive-by shootings are frequent, neighborhoods in which few outsiders go. All roads led to the Quad.

By the time I started investigating the ambush in 2007, the statute of limitations on the 1994 assault had lapsed. Police never attempted to find or question Tupac’s assailants. So I did. With guidance from street sources, I was able to determine who the assailants were and where they lived. I tracked them down in prison and interviewed them. Two of the men I suspected confirmed Tupac’s suspicions about who had set him up in hand-written letters mailed to me in the summer of 2007. One even offered to sell me Tupac’s stolen gold chain.

According to the assailants, the man who ordered and financed Tupac’s beating was a federal snitch and close associate of Sean Combs named James Rosemond, better known in hip-hop circles as Jimmy Henchman — a convicted felon of Haitian descent who bore a grudge against Pac.

Four years ago, I published an account of this critical 1994 Manhattan ambush, in which Pac was nearly killed. The entertainer was shot, punched, kicked and pistol-whipped by unknown assailants as he entered the Quad Recording Studios to which Henchman had invited him. The attackers were instructed not to kill Pac, just to rough him up. The assailants robbed the rapper of at least $40,000 in gold and diamond jewelry, and left him for dead. Shakur survived and publicly blamed Henchman for orchestrating the assault.

(A few years after the publication of my story, I learned, from the assailants, that it was Pac who shot himself, accidentally, in the groin, during the scuffle, with his own gun, attempting to defend himself. He got off only one round, they say, before they beat and pistol-whipped him to the ground, mercilessly, and proceeded to kick him again and again. There were no witnesses to the crime, so Pac, they say, used poetic license to dramatize it, transforming the assault into an assassination plot, exaggerating the number of times he was shot, and the severity of his wounds.)

My article, titled “An Attack on Tupac Shakur Launched a Hip-Hop War,” was published March 17, 2008 on the Los Angeles Times website. I based my piece on exclusive interviews with the men that attacked Shakur, who had never before spoken to a reporter, and with other New York gangsters familiar with the attack — all of whom verified the rapper’s assessment of who had set him up. The report was accompanied by FBI-302s I had obtained from a case file in a Florida court months after finishing my investigation, official documentation that supported some of what my interviewed sources had told me earlier.

On March 26, 2008, eight days after I broke my scoop, the FBI-302s were exposed as fakes by the website thesmokinggun.com — and all hell broke loose.

I should note here that it was not my idea to publish the documents on the Times website or to quote liberally from them in the article. That was a decision made by my editor and the Times‘ lawyer — and authorized by the then-editor in chief of the Los Angeles Times, boss of the entire newspaper.

My original draft barely mentioned the 302s or the individual who was later accused to have fabricated the documents. Information I had originally attributed to anonymous sources was later replaced by editors with the phrase “according to the FBI informant,” who made similar allegations in the purported 302s. The decision to rely on official documents, a common journalistic (legally defensive) ploy by editors and lawyers, sparked the scandal that killed the story.

The minute the FBI 302s were exposed as fakes, Henchman publicly accused me of fabricating documents to defame him. He claimed my piece was slanderous and had forever damaged his reputation. To me, it seemed comical that a convicted felon calling himself “Tha Gangsta Manager of Rap” could blame a story like mine for tarnishing his reputation.

After all, it wasn’t until Tupac accused Henchman of orchestrating the ambush in 1994 that anyone in the industry actually paid any attention to him. Indeed, Henchman built a name for himself on the strength of rumors of his involvement in the brutal assault, which bolstered his street credibility in the early 1990s. Before the Quad ambush, Henchman was just another scar-faced hustler with a rap sheet of arrests for murder, robbery and multiple gun violations. He had been indicted for cocaine trafficking — a case in which police said he had personally ambushed a man (foreshadowing the attack on Tupac), and shot him in the face.

He was, in fact, a fugitive from justice on the night he invited Tupac to the studio stemming from a gun violation tied to the previous ambush in a drug conspiracy case. Back then, Henchman billed himself as the high priest of gangsta rap’s anti-snitch crusade, and ran a talent agency that represented a small stable of rat-hating artists who rapped about drug dealing, shootouts, and killing. Before his arrest, his most high profile client was the popular Los Angeles rapper, Game. Authorities now believe that Henchman’s agency was, in fact, merely a front for a massive national drug enterprise.

Henchman and his lawyer, Jeffrey Lichtman, waged an aggressive online campaign attacking my credibility, calling for my firing on MTV and other media outlets. Why? I was not the first person to raise questions about Henchman’s involvement in the Quad attack. Before Tupac was shot to death in 1996, he blamed Henchman in published interviews and identified him by name as the perpetrator in his song, “Against All Odds.” Various music publications had run pieces speculating about Henchman’s possible role in the ambush — without reprisal.

But in my case, Henchman retaliated, with a coordinated personal attack against me that dominated the Internet for weeks. Henchman circulated lies about me online while his lawyer badgered my bosses at the Times with menacing calls. He Fed-Exed lawsuits he threatened to file, but never did. He didn’t have to. The Times caved into his bullying.

The fake-document scandal erupted at a moment when the LA Times was imploding financially and hemorrhaging red ink. With its parent company on the brink of bankruptcy, the newspaper was eliminating jobs, honing in on those who had worked the longest and were paid the most. Employees were offered “buyouts,” but it was clear that if they didn’t accept the terms set by management, they’d be fired with nothing at all. Hundreds of workers had already lost their jobs and a new wave of cutbacks loomed. Editors and lawyers knee deep in my legal battle might have fretted about their own professional futures.

Where did the documents come from? Late in 2007, long after finishing my street level investigation of the Quad ambush, I received an unsolicited tip by phone from a federal inmate named Jimmy Sabatino, who informed me that FBI-302 interview summaries referencing the Quad beating existed in a case he had filed in a U.S. District Court in Florida. Sabatino was in prison on a fraud conviction. I did not know him, but soon came to trust the inmate, after he helped steer me toward a handful of valuable (authentic) court records that I found in the National Archives and Records.

Acting on Sabatino’s Quad tip, I obtained the 302s from the Florida court because they contained information that supported some of what I had learned from my own sources. To me, the FBI paperwork was just icing on the cake, independent verification of my own investigation. My editor and the Times attorney were both thrilled that I had located privileged documents to reinforce my reporting. The 302s bore graphic design elements we had all seen before on FBI reports. I had no reason to believe they were fakes.

Journalists are trained specifically to seek out court documents because they are considered the most legitimate. Beyond reproach. The FBI reports in question had been scrutinized by a federal judge in an unrelated hearing in Florida and studied by layers of editors and lawyers at the LA Times. Not one person who saw them questioned their authenticity before my article came out. Not even Henchman’s lawyer, Jeffrey Lichtman, to whom I had faxed the 302s for review several weeks in advance of my story’s publication, questioned their authenticity.

Eight days after my piece ran, Bill Bastone, a former Voice reporter with expertise in East Coast FBI-302s, wrote an article for thesmokinggun.com, speculating that the documents were fakes.

His piece raised serious doubts in my mind about the authenticity of the documents. I didn’t know if he was right or not, but after hours of contemplation, I decided to trust Bastone’s judgment, and to take action.

On the morning of March 26, 2008, I arrived downtown early at the LA Times and immediately tried to convince my superiors into running a front-page follow-up in which I would acknowledge I had been duped by fake 302s, and apologize for my error. Initially, this idea was met with resistance from editors and lawyers who warned me it would be foolish to publicly admit an error. By noon, however, management changed its mind and assigned staff writer James Rainey to write the story as I had suggested. (That evenhanded piece ran under Rainey’s byline on March 27, 2008.)

To clarify: The only thing I apologized for was publishing purportedly fake documents. I never said that what I wrote was wrong. Someone may have tricked me, but the culprit did not undermine the thrust of what I reported. I would never have consented to publishing the 302s had they not supported what I had already learned in my own investigation. The substance of my article was accurate. Of this I was certain back then. I still am.

Colleagues suspected I had been set up. I’m no conspiracy theorist, but something that Henchman’s attorney said to MTV that week made me wonder: “Any first-year lawyer could see that the FBI 302 reports which formed the basis of the Times‘ story were fabricated.” First off, the alleged FBI documents did not form the basis of my article. My sources did. Secondly, Jeffrey Lichtman, the lawyer attacking the authenticity of the documents, had nearly three weeks to inspect the allegedly fake 302s before my story ran. I had faxed the 302s to him prior to publication seeking a response from Henchman or him to quote in the story. If it was so obvious that the documents were fabricated, did he not have a legal obligation to notify his client, and me, before the story came out?

Publicly, Henchman seized the moment, trying to twist my apology about the 302s into an exoneration of his role in the Quad ambush. The press ate it up. Privately, Lichtman threatened to sue the newspaper. I told The Times lawyers and editors that I welcomed the opportunity to take on Henchman in court. I was certain we would prevail and encouraged Times‘ management and legal advisors to let Henchman file suit.

Henchman’s lengthy rap sheet of arrests and convictions would have made it difficult for Tha Gangsta Manager of Rap to prove reputational damage. It also would have been tough for Henchman to explain why he had never sued any other publication for raising similar allegations. Henchman was aware that I had learned of other crimes he was involved in that I could expose in trial — unrelated to his masterminding of the attack on Tupac. I had documented evidence of additional criminal activity, I told the Times lawyers, and was confident that Henchman would not dare risk opening himself up to a public cross-examination.

At worst what I had done was make a mistake: I obtained what I thought were authentic 302s from a federal court. It was not premeditated or malicious on my part. It was an error. In fact, it was probably a set-up. Someone had gone so far as to illegally file fake documents in a federal court. I still have no proof that Sabatino made the phony documents, but if he did, it appears now that he did not act alone. Last year, an old friend of Henchman’s signed an affidavit (which Henchman circulated to the media) saying he had helped Sabatino fabricate the documents and file them in court.

Had the newspaper taken on Henchman in trial, we could have subpoenaed sworn testimony from everyone involved in my set-up and the Quad ambush itself. Should Henchman have actually filed, the suit would have presented us with an opportunity to do what officials never did: solve the crime, in a court of law.

Moreover, we had California Civil Code Section 47 on our side, a bulletproof law that permits journalists to publish and report upon any document filed in a judicial proceeding — even those later found to contain exaggerations, lies or fabrications.

Lawyers and editors rejected my recommendations, arguing it would be foolhardy to fight the case. The Times refused to defend the story in court. Instead, the paper crafted a retraction that sounded as if I had made up the entire story and sneaked it into print behind management’s back, without the knowledge, consent or guidance of senior editors and lawyers directly involved in its publication. I was pressured for days to accept the way the paper wanted to phrase its April 7 retraction. But it was not accurate. My sources were solid. My reporting was solid. It was just that the documents turned out to be a fake. The retraction made me sound like Jayson Blair or Janet Cooke. Nothing could have been further from the truth.

No reporter can publish anything that hasn’t been scrutinized by his newspaper’s editors and lawyers. The newspaper, not the reporter, decides what to publish and what not to publish. The April 7 “retraction” seemed designed to blame me to protect the jobs of the individuals who authorized my story to be published. It was not true, or even remotely close to what a true correction is supposed to be.

Following the retraction, scathing reports lit up the Internet, for weeks — lies and rumors that dog me to this day. I was attacked so many times in so many articles that Google actually contacted me and offered me an opportunity to respond. But the paper wouldn’t have it. I was ordered not to communicate with Google. I was also forbidden to return calls from reporters seeking comment. I was barred from addressing the avalanche of affronts online as well. Meanwhile, I waited for the Times to step up and defend me. The same people who praised me when I brought awards to the newspaper failed to offer any defense for a conscientious reporter who, at worst, had made an honest mistake — my first in 18 years.

Despite their failure to defend my story, top editors at the newspaper privately assured me my job was safe. Beyond those promises, on the Wednesday before the next wave of layoffs was to be announced, I asked the newly appointed editor of the section in which I worked if I had anything to worry about. She said no. Two days later she called me back into her office, and told me she had misspoken. The paper, she said, had just decided to let me go.

I was laid off the same afternoon that Henchman agreed to sign a secret out-of-court settlement with the Times. I was allowed to apply for a buyout and informed that I could tell people it was my own decision to leave. My termination was widely viewed as a nod to Henchman.

Before turning in my parking pass, I was informed that the Times had paid Henchman $200,000 in cash. That’s not what Henchman said. He boasted about walking away with half a million, plus my head on a platter, as if he had been vindicated. He announced my ouster on his website before I left the Times. (Last week in court, Henchman’s attorney said in court that the settlement had paid him $250,000.)

The campaign by Henchman to divert attention from the Quad ambush did not subside after my dismissal. In October 2010, four months after I left the LA Times, Henchman escalated his efforts to discredit me by fabricating a lawsuit and distributing copies of it to scores of media outlets, falsely stating that he had sued me for $120 million. Henchman’s phony suit alleged that I had again plotted to defame him, this time with a New York Daily News reporter who published a story in September 2010 alleging he was a federal informant.

I have never worked for the New York Daily News. The Daily News article was based on court documents its reporter obtained herself from official archive records of Henchman’s own criminal cases that proved he was an informant.

After the Daily News piece came out, Henchman’s attorney immediately lashed out at authorities, calling the article “nothing short of a targeted assassination attempt by the government.” But it didn’t take long for Henchman to shift the blame to me, claiming that the paperwork on which the article was based was fabricated — and somehow it was my fault.

Shortly after the Daily News ran its Henchman expose, a new fanzine suddenly appeared on the Internet. It was called hiphopconspiracy.com. It was supposed to be a real publication reporting news about the inside world of rap. In fact, it is nothing but a vehicle to spread lies about me. The first link at the top of the site’s first page is “Chuck Philips.” Click on my name and you’ll be led to a fake $100-million libel suit against me that has never been filed in any court, plus an array of other fictitious legal documents created to tarnish my reputation. (On May 25, less than a week after this story first appeared, Go Daddy stripped the website of all its fake anti-Philips documents.)

Henchman provided copies of this phony litigation to Vibe magazine and other rap publications. Vibe published the bogus lawsuit, despite the fact that it clearly

bears no date or court stamp, and apes exact language from the mock claim Henchman used to threaten the LA Times.

The fake 302s weren’t the reason Henchman and others wanted me fired. Looking back on it now I’m guessing that they were less concerned about what I had already uncovered than about what I was certain to find out, should I be allowed to keep digging. Henchman had reason to be nervous. He knew I was communicating directly with his ex-partners in crime — old friends privy to his most damning secrets. I had crossed bridges he burned long ago. His ex-pals not only knew that the leader of rap’s anti-snitch underground was, in fact, a snitch. They told me that Henchman had bigger skeletons hiding in his closet.

Last summer, DEA agents picked up Henchman’s brother in Atlanta on felony drug trafficking charges. By autumn, the feds had arrested another Henchman associate for smuggling large amounts of cocaine from Los Angeles to New York. Authorities arrested the associate’s wife as well after finding a loaded 9-mm handgun, an Intratec Tec-9, several loaded magazines and boxes of ammunition, plus $39,500 cash stashed in her Mercedes Benz.

In early June 2010, the DEA issued a warrant for Henchman’s arrest on charges of cocaine trafficking. Henchman released a statement blaming his problems on overzealous prosecutors and on me, but promised to turn himself in. He went on the run. On June 21, he was arrested following a dramatic foot chase outside the posh W Hotel in Manhattan. The feds charged him with crack cocaine trafficking, obstruction of justice, money laundering and arrested two of his cronies for a hit masterminded by Henchman. The murder victim had dared to humiliate Henchman by slapping his son in broad daylight in front of Henchman’s own talent agency. (Henchman has since been charged with murder.)

Seven months ago, Jeffrey Lichtman, whose claim to fame is that he once represented mafia don John Gotti’s son, was disqualified as Henchman’s lawyer. The court ruled he had a conflict of interest. In the past, Lichtman represented some of Henchman’s co-defendants.

Days before Henchman’s arrest last summer, his former best friend, Dexter Isaac, the convict who led the attack at the Quad in 1994, confessed publicly that it was Henchman who hired him to rob and pistol-whip Tupac. Dexter, who has known Henchman since they were 14, was the lead source for my 2008 Quad story. He is one of a handful of disgruntled street soldiers who taught me how to navigate the treacherous world of Jimmy Henchman.

“In 1994, [Jimmy Henchman] hired me to rob 2Pac at the Quad Studio. He gave me $2,500, plus all the jewelry I took, except for one ring, which he wanted for himself. It was the biggest of the two diamond rings that we took. I still have as proof the chain that we took that night in the robbery.

“Now I’m not going to talk about my friend Biggie’s death or 2Pac’s death, but I would like to give their mothers’ some closure. It’s about time that some one did, and I will do so at a different time. Jimmy, you and Puffy like to come off all innocent-like, but as the saying goes: you can fool some of the people some of the time, and all of the people some of the time, but you cannot fool all of the people all of the time.”

Dexter’s revelation caused a shit storm, and was picked up by news outlets everywhere: The Washington Post, the New York Times, the Wall Street Journal,

the Baltimore Sun, the New York Post, LA Weekly and scores of publications around the world.

Even though Dexter singled me out in his statement — “[Jimmy Henchman] has crucified good reporters like Chuck Phillips, at the LA Times, for telling the truth about him and his activities” — the LA Times didn’t blink. They buried Dexter’s confession in a tiny throwaway reprint deep inside the newspaper’s entertainment feature section.

Further dismissing Dexter’s defense of my reporting, LA Times management leaked a backhanded slap at me: “Nothing has happened since 2008 to warrant withdrawing or revising the [April 7] retraction,” the Times said in a statement issued last October to the LA Weekly. “No new information has emerged that bears on the mistakes for which we apologized and which we retracted.”

By not acknowledging Dexter’s confession, the LA Times avoided having to admit it made a mistake. The April 7 retraction not only tarnished my reputation, but rendered me virtually unemployable, inside and outside the world of journalism. I’ve been turned down for hundreds of reporter jobs.

New York literary houses loved a proposal I wrote for a book about the murders of Tupac and Biggie, but declined to publish the book after Googling me and reviewing the April 7 retraction in the LA Times.

Likewise, the Columbia Journalism Review spiked an essay I wrote about the April 7 retraction after its executive editor received a phone call from the LA Times — just moments before the essay was scheduled to be published. The editor says the Times did not influence his decision to yank it.

My 2008 scoop about the Quad ambush has since been proven to be accurate. But the LA Times remains uncontrite.

How could the true-life public confession of Tupac’s 1994 assailant be met with such apathy?

We asked for, and received, this statement from the Los Angeles Times about the retraction of Philips’ story — T.O.

We retracted Chuck Philips’ March 17, 2008, article concerning an attack on rap star Tupac Shakur because we learned that documents and sources he relied on didn’t support the article. Specifically, supposed FBI documents regarding the 1994 attack on Shakur turned out to be forgeries. The man who supplied the documents, James Sabatino, also provided significant additional information that was included in the article, attributed to an anonymous source. As Chuck and his editors later discovered, what Sabatino had told him was fabricated.Under these circumstances, we had no alternative but to acknowledge the mistake, apologize to our readers and retract the article. Nothing has happened since then to warrant withdrawing or revising the retraction. No new information has emerged that bears on the mistakes for which we apologized and which we retracted.