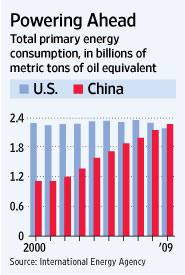

China Passes U.S. as World’s Biggest Energy Consumer

China has passed the U.S. to become the world’s biggest energy consumer, according to new data from the International Energy Agency, a milestone that reflects both China’s decades-long burst of economic growth and its rapidly expanding clout as an industrial giant.

China’s ascent marks “a new age in the history of energy,” IEA chief economist Fatih Birol said in an interview. The country’s surging appetite has transformed global energy markets and propped up prices of oil and coal in recent years, and its continued growth stands to have long-term implications for U.S. energy security.

The Paris-based IEA, energy adviser to most of the world’s biggest economies, said China consumed 2.252 billion tons of oil equivalent last year, about 4% more than the U.S., which burned through 2.170 billion tons of oil equivalent. The oil-equivalent metric represents all forms of energy consumed, including crude oil, nuclear power, coal, natural gas and renewable sources such as hydropower.

China, meanwhile, disputed the IEA figures, but didn’t offer alternative data, according to Zhou Xian, spokesperson for China’s top energy agency.

The U.S. had been the globe’s biggest overall energy user since the early 1900s, Mr. Birol said.

China overtook it at breakneck pace. China’s total energy consumption was just half that of the U.S. 10 years ago, but in many of the years since, China saw annual double-digit growth rates. It had been expected to pass the U.S. about five years from now, but took the top position earlier because the global recession hit the U.S. more severely, slowing American industrial activity and energy use.

China’s economic rise has required enormous amounts of energy—especially since much of the past decade’s growth was fueled not by consumer demand, as in the U.S., but from energy-intense heavy industry and infrastructure building.

China’s growing energy demands will present new challenges to U.S. foreign policy, as well as to international efforts to reduce emissions of greenhouse gases linked to climate change. China National Petroleum Co., the country’s biggest oil company, is pushing forward with oil and gas projects in Iran, despite U.S. efforts to enforce sanctions against the Tehran government.

Beijing has refused to agree to cap its overall growth in its consumption of fossil fuels, or reduce its emissions of carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases. That frustrated President Barack Obama’s efforts to forge an international climate agreement at a United Nations summit in Copenhagen last December.

China instead set a target to reduce emissions intensity—the amount of carbon dioxide emitted per unit of gross domestic product—by 40% to 45% from 2005 levels by 2020. That meant China was agreeing to make its economy more energy efficient—boosting its competitiveness—but not to consume less energy overall.

China’s growth has transformed global energy markets and sustained higher prices for everything from oil to uranium and other natural resources that the country has been consuming. Once, China was a major exporter of both oil and coal. Its increasing reliance on imports has sustained higher energy prices worldwide and underpinned a natural-resource boom in Africa, the Middle East and Australia.

“There is little doubt that China’s growing consumption changes what ability we have to control our own destiny within global energy markets,” said David Pumphrey, a senior fellow at the Center for Strategic and International Studies. “China can now demand a large space inside any energy-policy tent.”

China’s rapidly expanding need for energy promises to have major geopolitical implications as it hunts for ways to satisfy its needs. Already, China’s rising imports have changed global geopolitics. Chinese oil and coal companies have been looking overseas in their quest to secure energy supplies, pitching the Chinese flag in places like Sudan, which Western companies had largely abandoned under international pressure.

The most ambitious effort to secure overseas energy supplies was the failed 2005 attempt Cnooc Ltd. to take over California-based Unocal in an $18 billion bid, which was trumped by politics and rival Chevron. Despite a short pullback in the aftermath of that failed deal, Chinese companies have expanded overseas, buying assets in Central Asia, Africa, South America, Canada and even small stakes in the Gulf of Mexico. While their overall overseas footprint is still small compared with that of big international oil companies, these companies are expanding with access to cheap credit through China’s state-owned banks.

Voracious energy demand also helps explain why China—which gets most of its electricity from coal, the most polluting of fossil fuels—passed the U.S. in 2007 as the world’s largest emitter of carbon-dioxide emissions and other greenhouse gases.

In the past, being the world’s biggest consumer of fossil fuels went hand in hand with being its dominant economy. The question now is whether this will hold true in the future, as nations compete to develop new ways to produce more wealth with less energy. While China is No. 1 in consumption, the U.S. remains the world’s biggest economy.

The U.S. is also by far the biggest per-capita energy consumer, with the average American burning five times as much energy annually as the average Chinese citizen, said Mr. Birol.

The U.S. also remains the biggest oil consumer by a wide margin, going through roughly 19 million barrels a day on average. China, at about 9.2 million barrels a day, runs a distant second. But many oil analysts believe U.S. crude demand has peaked or is unlikely to grow very much in coming years, because of improved energy efficiency and more stringent vehicle fuel-efficiency regulations.

China’s rise is also helping shift the focus for oil producers in the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries. Key OPEC states like Saudi Arabia long looked to U.S. oil consumption for guidance in adding new pumping capacity. But in recent years, OPEC states including Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates have built or started building refineries and storage facilities in Asia. Saudi Arabia, the world’s biggest crude exporter, now ships more to China than to the U.S.

Prior to the global economic crisis, China had been expected to become the biggest energy consumer in about five years. Economic malaise and energy-efficiency programs in the U.S. brought forward the date, Mr. Birol said.

The decreased “energy intensity” of the U.S. economy is a key reason energy investors, such as General Electric, have increasingly looked to China as a driver of growth. Mr. Birol said China requires total energy investments of some $4 trillion over the next 20 years to keep feeding its economy and avoid power blackouts and fuel shortages.

Mr. Birol, formerly an economist at OPEC, said China is expected to build some 1,000 gigawatts of new power-generation capacity over the next 15 years. That is about equal to the current total electricity-generation capacity in the U.S.—a level achieved over several decades of construction.

China’s energy intensity actually fell during the first phase of its economic growth in the 1980s and 1990s, which was driven by light manufacturing. But in the early 1990s, China became a net oil importer for the first time as its demand finally outpaced domestic supplies. China’s energy demand surged again after China joined the World Trade Organization in 2001.

Before China joined the WTO, most international prognosticators, including the IEA, predicted energy demand would increase at an annual rate of 3% to 4% from 2000 to 2010. Demand wound up growing four times faster than they predicted.

There is a chance the growth in China’s energy appetite could slow, as the pace of industrial expansion slows and energy-efficiency policies backed by the government—such as tougher fuel-efficiency standards for cars—take hold.

In a few years, there won’t be much infrastructure left to build. Urbanization will continue, but at a slower pace. And the heavy factory jobs that consume huge amounts of energy may start to shift away to other countries partly as China’s workers demand better conditions and higher salaries.

But the same force that could be moving factory jobs away—rising incomes—could also underpin even greater energy needs as richer Chinese start consuming more. The question is whether China will adopt a low-energy pathway pioneered by places like Japan and Europe or follow a high-energy life-style of big houses and big cars pioneered by the U.S.